The work of Nigerian woman artist Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu (1928–2003) offers a window into cultural representations of African men and women in postcolonial Nigeria. In what was a male-dominated art scene in the 1960s, Ugbodaga-Ngu stood out not only because of her visual production, but also because of her intellectual involvement as a faculty member at the Nigerian College of Art, Sciences and Technology (renamed Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria in 1962). Despite her contribution to the history of modernist art, little has been published on her role in the advancement of art during this period or on her far-reaching influence as an art educator. This post feature foregrounds Ugbodaga-Ngu’s role in the structural development of art in Nigeria, the themes that were of particular interest to her, and how she represented cultural identity, practice, and experience in her painting.

Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu was born in Kano, Nigeria, in 1928. Although most biographies state that she was born in 1921 and died in 1996, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium: Historian, Builder, Aesthetician and Visioner (2004) notes that she was born in 1928 and died in 2003. 1See Daniel Olaniyan Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium: Historian, Builder, Aesthetician and Visioner, (Abuja: National Gallery of Art, 2004), 34. This source is likely to be more accurate, not just because it was documented by a professor of art history in the university where she first worked as a faculty member, but because it is aimed at filling a research gap on the biographies of Nigerian artists. Ugbodaga-Ngu taught art in mission schools from 1945 to 1950, when she received a scholarship from the colonial administration to study art at the Chelsea School of Art in London. Four years later, in 1954, she received a National Diploma in Design, with a distinction in painting. A year after that, in 1955, she was awarded an Art Teacher’s Diploma from the Institute of Education, University of London. She was a contemporary of Ben Enwonwu (Odinigwe Benedict Chukwukadibia Enwonwu, 1917–1994), though their work is equally good, hers did not receive the same critical attention because it had been produced by a woman. This is, however, not to deny that some narratives accompany her rarely seen work in galleries, but they are mostly dispersed.

As an art educator, artist, and arts administrator, Ugbodaga-Ngu contributed to advancing modernism in Nigerian art in the mid-twentieth century and its elaboration in the decades that followed. 2It is important to note that Nigeria was under the British colonial rule until independence movement began to call for her political independence, which happened on October 1, 1960. She was the first Nigerian artist-intellectual and woman appointed to teach the first and second generations of art students at the site of the former Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology, now Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria (ABU), where she was a faculty member from 1955 to 1964. At the beginning of her career at ABU, she was not popular with her white colleagues, “who felt, she was not supposed to be there.” 3Simon O. Ikpakronyi, “Timothy Adebanjo Fasuyi: The Doyen of Zaria Art School,” in Timothy Adebanjo Fasuyi: A Renowned Artist and Accomplished Educationist, ed. Abdullahi Maku and Simon Ikpakronyi (Abuja: National Gallery of Art, 2018), 16. However, she remained committed to her work during this period, as she taught Life Drawing, Imaginative Composition, and Painting. Ikpakronyi, 4“Timothy Adebanjo Fasuyi,” 16. In 1959, she was awarded a Ford Foundation Fellowship that enabled her to accept a lecturership at the Institute of Education at the University of Ibadan. 5Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 34. Later, she served as a temporary part-time research fellow at the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ife where, in 1964, she wrote a paper on Yoruba ibeji carvings. 6Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 34.

After her departure from Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria for some years, Ugbodaga-Ngu resumed teaching at ABU again after 1966, having raised her four children—three boys and a girl. 7Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 35. She continued to lecture at ABU in the 1970s, before Solomon Wangboje (1930–1998) was head of the Department of Fine Arts at the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria (1972–75). 8Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 35. This is significant because it draws attention to a period when she probably left ABU again. Apart from teaching, in 1975, she served as a state advisor to the Second Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC 1977), a pioneering Nigerian festival held in Lagos in 1977 to celebrate Black artists from across Africa and its diaspora. This event was significant in the advancement of art beyond academia in Nigeria and on the African continent at large. She returned to lecturing at the University of Benin in 1980 during Professor D. W. A. Baikie’s tenure as vice-chancellor (1979–85). 9Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 35.

In 1959, as part of the effort to expand and nationalize the curricular offerings in the ABU art department, Ugbodaga-Ngu invited Ben Enwonwu to deliver a lecture on contemporary Nigerian art and Timothy Adebanjo Fasuyi (born 1935), her former student, to speak on traditional Nigerian art. 10Chika Okeke-Agulu, Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 82. These presentations set the decolonizing stage—along with efforts by other African intellectuals and artists such as Iba N’diaye (1928–2008) and Papa Ibra Tall (1935–2015), both of Ecole National des Beaux-Arts in Senegal, and Francis Nnaggenda (born 1936) of Makerere Art School in Uganda. 11The modernist art scene on the African continent in the 1950s and 1960s drew its inspiration from European conventions of representation in combination with African forms and African artistic heritage and cultures. This amalgamation was championed by African artist-intellectuals and their students, and others like President Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal, who inspired the Négritude movement, and Kwame Nkruma of Ghana, who promoted Pan-Africanism.

This was a period when attempts were being made to create national identities and public cultures that would reflect a distinctively African art. In Nigeria, as a result, artistic practice increasingly focused on aspects of Nigerian cultural and artistic heritage, albeit infused with European technique. Ugbodaga-Ngu’s first generation of students, which included Timothy Adebanjo Fasuyi, Solomon Wangboje, Uche Okeke (1933–2016), Yusuf Grillo (1934–2021), Demas Nwoko (born 1935), Simon Okeke (1937–1969), Bruce Onobrakpeya (born 1932), and William Olaosebikan, among other pioneers, went on to form the Zaria Art Society. Not all of them opposed the imported curriculum and colonial imprint of the Royal College of Art. What they universally rejected, however, was their British lecturers’ abhorrence of the incorporation of African art references in their work. 12Sule James, “Tribute to Yusuf Grillo: Nigerian art activist, scholar and bridge builder, “ September 8, 2021, The Conversation. In response, they drew upon diverse African cultural and aesthetic traditions in decolonizing visual practice they defined as “natural synthesis.”

Ugbodaga-Ngu’s educational qualifications and status as an intellectual were far-reaching in their influence. Many of her students obtained certificates in art education, or the so-called Art Teacher’s Diploma, upon completing their training in art. 13Ola Oloidi, “Growth and Development of Formal Art Education in Nigeria, 1900–1960,” Transafrican Journal of History 15 (1986): 123. Recollecting the impact of his teachers on his artistic development, Kolade Oshinowo (born 1948), who studied painting at ABU from 1968 to 1972, observed that he was fortunate to have “serious and dedicated lecturers like Professor Charles Argent, Mrs. Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu, [and] Messrs. Mike Tailor and Clary Nelson-Cole.” Oshinowo further expressed, “These are people who helped me a great deal in laying the foundation upon which my practice is built today.” 14Changing Times: An Exhibition of Works by Kolade Oshinowo, exh. cat. (Onike, Yaba, Lagos: Kolade Oshinowo, 2016), 19. His reference to Ugbodaga-Ngu, in particular, stresses how much she contributed to shaping the direction of his creative process.

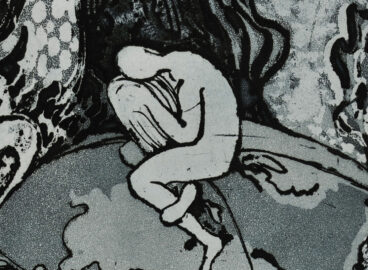

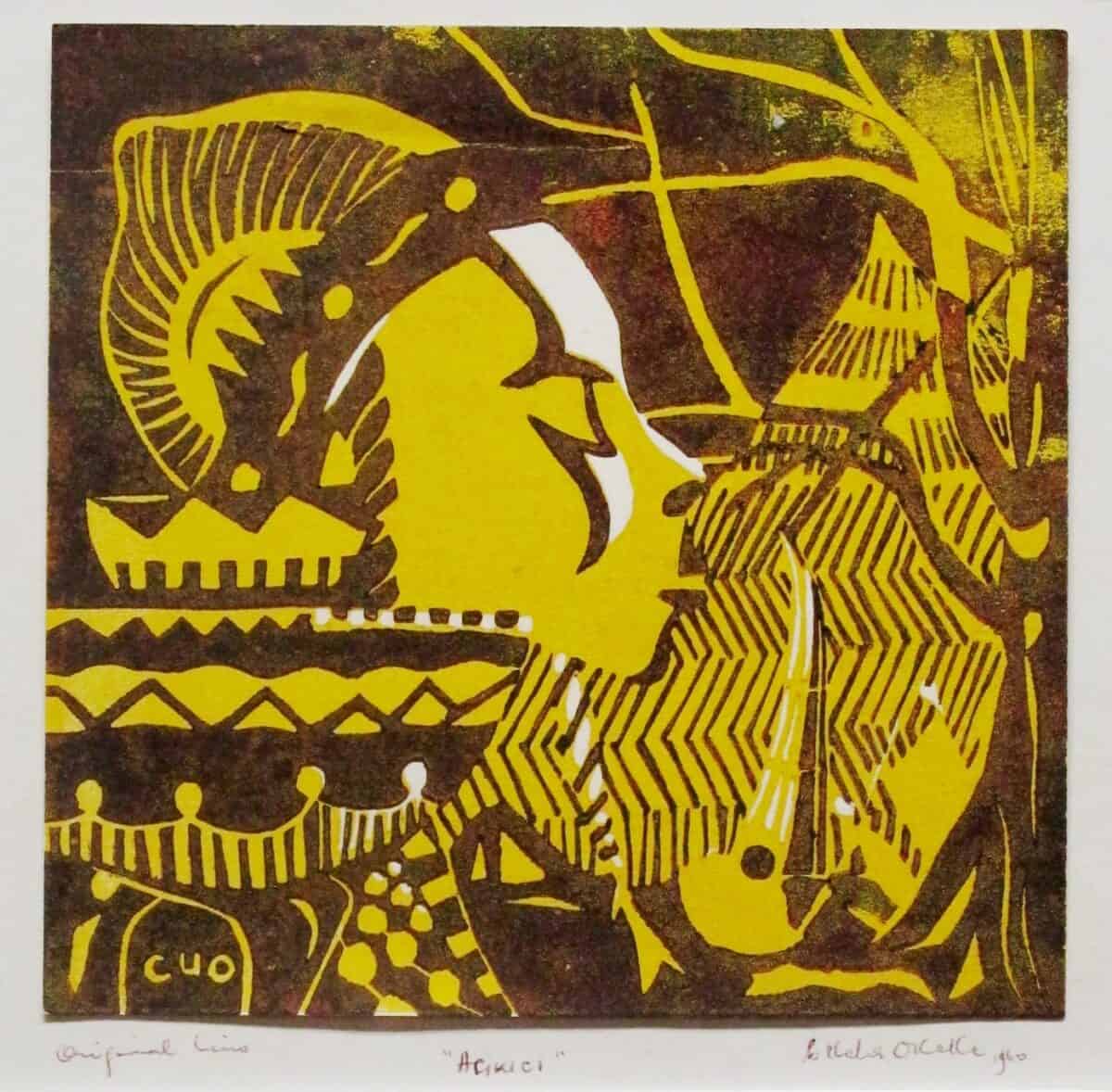

An image of a Fulani milkmaid titled Agwoi (1960) by Uche Okeke, one of Ugbodaga-Ngu’s students, references the vernacular term used to describe people of Fulani descent in Nigeria. The invocation of a milkmaid in Fulani culture reflects the concept of “natural synthesis” in its referencing of not just the maid’s braided hair which highlights a mode of body beautification and adornment, but the intricately decorated calabashes used for collecting and storing cow milk for the day’s business.

Apart from the contributions discussed above, Ugbodaga-Ngu played other significant roles in the development of modernist art in Nigeria. She featured as a regular television guest artist in Ibadan in the 1960s, and participated in several group exhibitions in Europe and the United States. She had solo exhibitions in London 1958, in Lagos and Ibadan in 1959, in Boston in 1963, and again in Ibadan in 1964. 15Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 34, 35.

During this time, she developed her own idiosyncratic language; one influenced not only by European art tradition, but also by African motifs and forms drawn from different cultures in northern and southern Nigeria. Some of her works of this period combine the vitality of the northern Nigerian aristocrat with the vivacious and sensuous festival dancers of southern Nigeria, producing in some cases, tension, and in others, repose and calm. 16Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 35. The dominant aesthetic formation of the postcolonial era in Nigeria, as elsewhere on the African continent, took African culture as its paradigm. Some of the major ideologies that shaped this aesthetic were Pan-Africanism, Négritude, and Natural Synthesis. These movements were integral to decolonization and, ultimately, to independence. Although Ugbodaga-Ngu’s paintings are not easily accessible, the few that can be traced indicate her alignment with this paradigm.

Close inspection of her work reveals that she also drew inspiration from Hausa cultural traditions and the lived experience of diverse people in northern Nigeria. This is evident in the range of thematic preoccupations expressed in her paintings, in works such as Abstract (1960), Market Women (1961), and Beggars (1963). Other works, including Palm Wine Seller (1963) and Dancers (1965),reference cultural practices and festival scenes from southern Nigeria.

Abstract, a highly textural painting, boldly explores color and shapes adopted by European artists in their exploration of African shapes and forms. One Western artist whose style possibly inspired Ugbodaga-Ngu was Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), largely because “Picasso [was] an all-encompassing symbol in the minds of many African artists.” 17Sidney Littlefield Kasfir, Contemporary African Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999), 128. Despite this stance, Ugbodaga-Ngu did not emulate his style, but rather drew inspiration from the Andalusian to define her own form of abstraction. Her peculiar individual style is evident in this painting, in which she applied the lessons of cubism to her own composition. The picture plane reveals the arrangement of diverse geometric shapes and forms, suggestive of a bull in its rich, earthy color palette but equally evocative of traditional African art in its sculptural forms. The bull’s two “horns” are rendered as thick curved lines, and the animal appears to be in a restive position. This subject matter might have been inspired by Picasso’s bull series and also scenic views of bulls in the northern Nigerian landscape. The sight of cattle is an everyday experience for people who live in the north, and Fulani herders grazing cattle or bulls owned by Hausa households are likewise common.

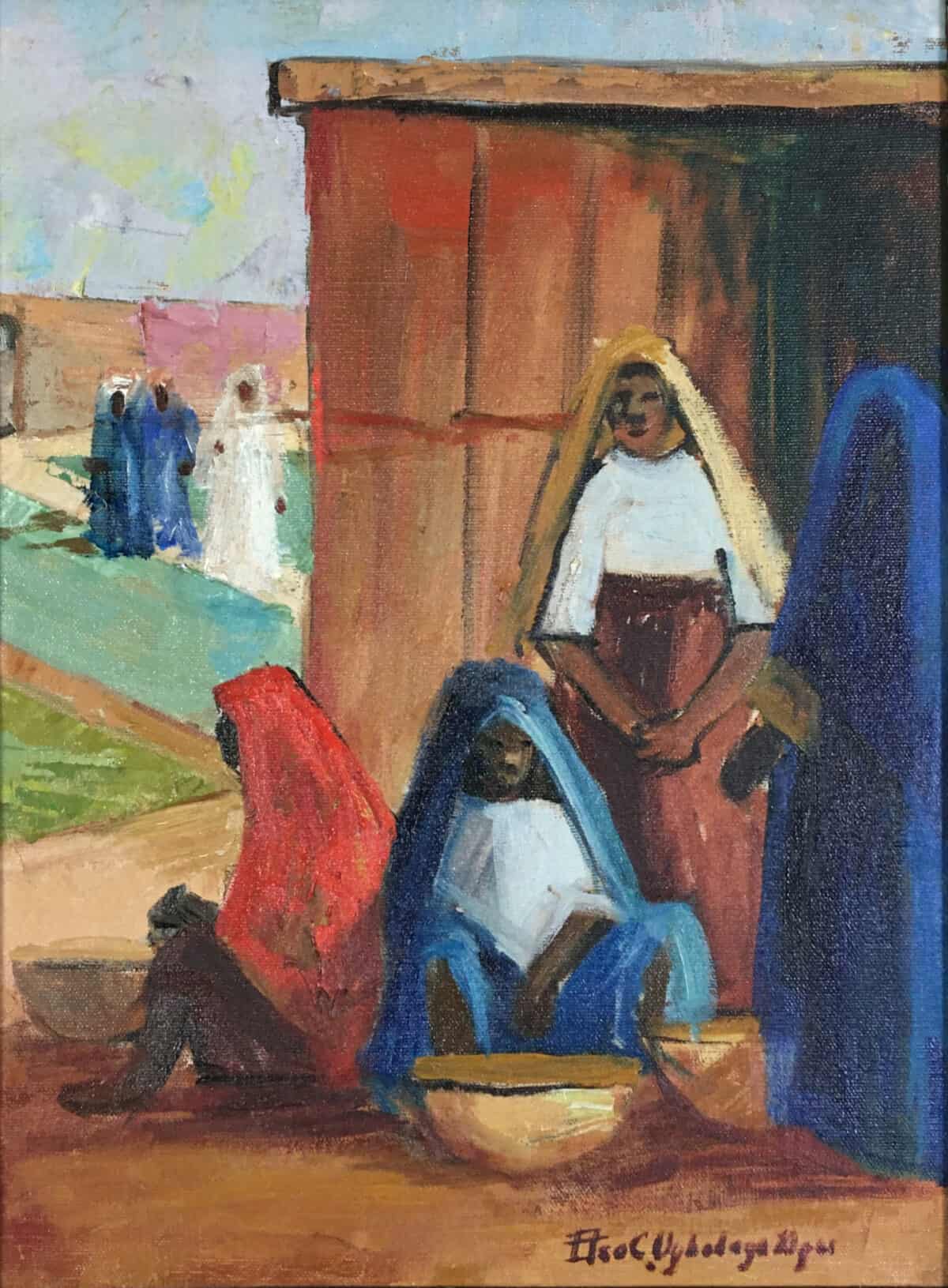

Market Women (1961) signals the construction of gendered social identity, drawing attention to the socioeconomic activity of the market. Ugbodaga-Ngu used expressionistic brushwork to depict four women: two seated and two standing. Adorned in veils, blouses, and dark wrappers of different colors, they are arranged in the foreground, set against the brown wall of a shop or stall. Chiaroscuro models and defines their bold forms. Ugbogada-Ngu successfully depicted the drapery of their veils and wrappers, the folds and textures of which are highlighted. Their activity, in turn, is suggested by their bowls—calabashes used for the storage of the milk and millet meal sold by Hausa/Fulani milkmaids in northern Nigerian markets. The depiction of these women engaged in work is offset by a group of three men in the distance who, presumably customers are walking toward them and the market. The contrasting portrayals of the men and women highlight the differing gender roles.

The sartorial details also date the activity. Given that the women use veils, as opposed to hijabs to cover themselves. Research reveals that the hijab was adopted in the late 1970s and 1980s as a result of cultural encounters and exchange with Arabs. 18Sule Ameh James, “Intersecting Identities: Interrogating Women in Cultural Dress Forms in Contemporary Nigerian Paintings,” March 16, 2021, African Identities, https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2021.1899895. Thus, Ugbodaga-Ngu did not merely reflect on the economic activity of these women but their cultural attires in a likely scene from the 1960s.

Beggars (1963) introduces a nuance in the construction of sociocultural identity among a group of people in northern Nigeria. This particular scene is dominated by a blue background, and three figures arranged in the center of the composition. They are dramatically highlighted with sharply contrasting light and shade. The figure on the left sports a cap while the center and right-hand figures are wearing hats. Their clothing is characteristic of that of mendicants in Hausa/Fulani culture. The men’s hats hint at cultural elements adopted to provide shade as their wearers move from street to street under the hot sun.

In her painting, Ugbogaga-Ngu draws attention to the history of mendacity among men, women, and children forced into vagrancy as a means of livelihood. Indeed, in an attempt to engage elements from indigenous African art, she depicts the three beggars engaged in the act of singing, a cultural practice of Muslim minstrels, who perform satiric operas as they go about begging. Given the fact that Ugbodaga-Ngu was a faculty member at the ABU, Zaria, she must have been witness to and influenced by these groups, as she reflected on modernity in Hausa society. Although the subject is mendicants, the painting does not depict begging as such, but rather the musical performance of oral beggar poets or almajirai. 19The Hausa word “Almajirai” is derived from the Arabic word “al-Muhajir,” which refers to a person who migrates from his home in search of Islamic knowledge. Colloquially, the term has expanded to refer to any young person who begs on the streets and does not attend secular school. These Hausa minstrels do not use musical instruments to accompany their street poetry.

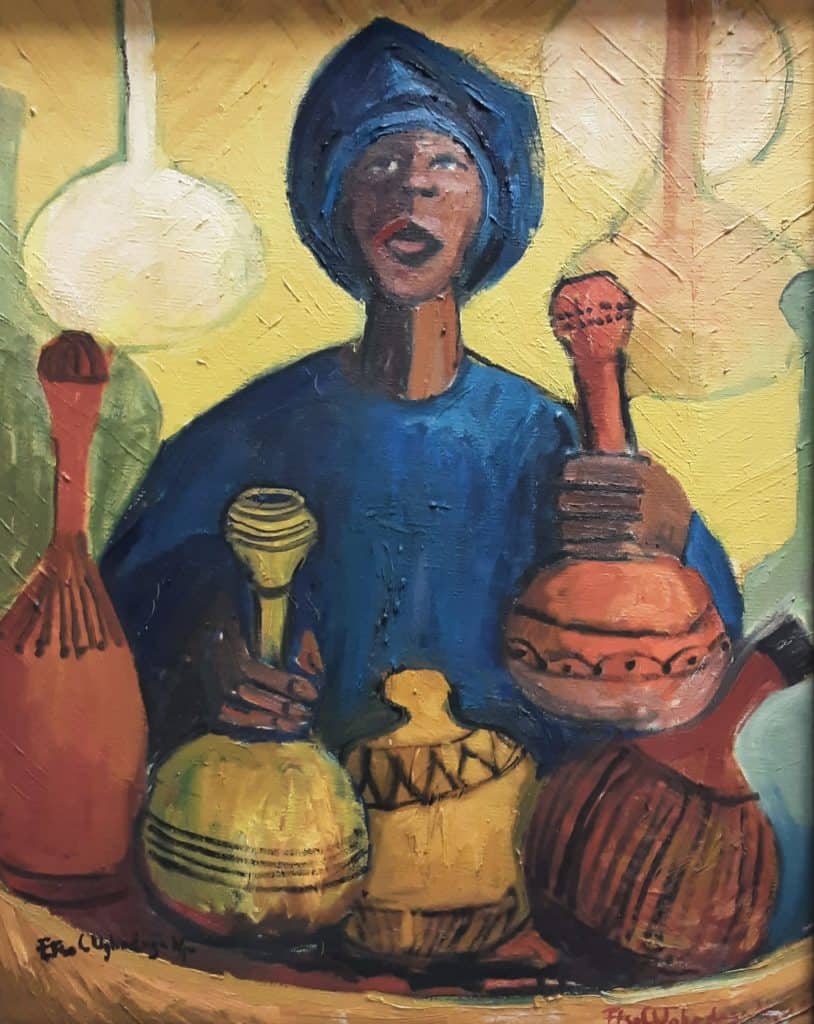

A colorful or polychromatic portrayal of a woman adorned in a blue gele and buba, the cultural dress of the Yoruba, Palm Wine Seller (1963) features calabash motifs in the foreground, and as shadows in tones of green and yellow in the background. In front of the vendor, there are five intricately designed calabashes filled with palm wine. Ugbodaga-Ngu has portrayed the woman holding two of the vessels, attempting to present them to customers in front of her as is suggested by her upward gaze. Although the thematic thrust of this painting constructs the identity of an individual selling palm wine, its content draws attention to one of the economic activities of women in Yoruba culture: she is likely the wife of a tapper or a vendor whose trade is selling the beverage. Palm wine is a natural alcoholic drink produced from the fermented sap of various palm trees. Common throughout West Africa, it has social and cultural value in many rural and urban areas in southern Nigeria. Together with Market Women, this painting highlights Ugbodaga-Ngu’s interest in depicting the various economic activities and roles of women in Nigeria in the 1960s—that is, their noble and industrious engagement in supporting their households.

Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu played numerous roles in advancing postcolonial modern art in Nigeria, becoming an inspiration not only to her students, but also to other Nigerian art teachers and artists. Even though she depicted figures in her work, in many instances, she moved away from a realistic figurative style, blending Western and Nigerian traditions, forms, techniques, and ideas to create fresh modernist work. Not only did she develop and excel at a representational style adopted by early modernist artists, she also contributed to portraying the lived experiences of men and women, drawing attention to aspects of modernity in Nigeria in the 1960s. Her compositions manifest the cultural dress associated with African identity and the cultural differences among people in northern and southern Nigeria. Her work communicates different thematic concerns that convey her thoughts on individual and Nigerian cultural identities, and social and cultural values among people in northern and southern Nigerian cultures.

In reproducing the images contained in this text, the Museum obtained the permission of the rights holders, whenever possible. If the Museum could not locate the rights holders, notwithstanding good-faith efforts, it requests that any contact information concerning such rights holders be forwarded so that they may be contacted for future editions.

- 1See Daniel Olaniyan Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium: Historian, Builder, Aesthetician and Visioner, (Abuja: National Gallery of Art, 2004), 34.

- 2It is important to note that Nigeria was under the British colonial rule until independence movement began to call for her political independence, which happened on October 1, 1960.

- 3Simon O. Ikpakronyi, “Timothy Adebanjo Fasuyi: The Doyen of Zaria Art School,” in Timothy Adebanjo Fasuyi: A Renowned Artist and Accomplished Educationist, ed. Abdullahi Maku and Simon Ikpakronyi (Abuja: National Gallery of Art, 2018), 16.

- 4“Timothy Adebanjo Fasuyi,” 16.

- 5Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 34.

- 6Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 34.

- 7Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 35.

- 8Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 35.

- 9Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 35.

- 10Chika Okeke-Agulu, Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 82.

- 11The modernist art scene on the African continent in the 1950s and 1960s drew its inspiration from European conventions of representation in combination with African forms and African artistic heritage and cultures. This amalgamation was championed by African artist-intellectuals and their students, and others like President Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal, who inspired the Négritude movement, and Kwame Nkruma of Ghana, who promoted Pan-Africanism.

- 12Sule James, “Tribute to Yusuf Grillo: Nigerian art activist, scholar and bridge builder, “ September 8, 2021, The Conversation.

- 13Ola Oloidi, “Growth and Development of Formal Art Education in Nigeria, 1900–1960,” Transafrican Journal of History 15 (1986): 123.

- 14Changing Times: An Exhibition of Works by Kolade Oshinowo, exh. cat. (Onike, Yaba, Lagos: Kolade Oshinowo, 2016), 19.

- 15Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 34, 35.

- 16Babalola, The Nigerian Artist of the Millennium, 35.

- 17Sidney Littlefield Kasfir, Contemporary African Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999), 128.

- 18Sule Ameh James, “Intersecting Identities: Interrogating Women in Cultural Dress Forms in Contemporary Nigerian Paintings,” March 16, 2021, African Identities, https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2021.1899895.

- 19The Hausa word “Almajirai” is derived from the Arabic word “al-Muhajir,” which refers to a person who migrates from his home in search of Islamic knowledge. Colloquially, the term has expanded to refer to any young person who begs on the streets and does not attend secular school.